(This is the textual version of my video on the YouTube channel for this Blog, Zen and the Art of Software Development)

Let’s start with admitting that we’re in an “AI Bubble”; We have almost daily announcements on new AI related products, or predictions on where we are heading with them. A large part of the product announcements are not for things that we can actually get and use now, but rather for the “in development” or “in research” ones, which (reality check) doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll eventually get them. The products that we do get, don’t always fully deliver on their promises, but again that is normal, given that we need to filter out the “marketing speak”. This should not surprise us, and any acknowledged or claimed limitations invariably end up in the “really soon now” lists. The really interesting predictions are those that are based on current or proposed research, because this is where creativity is actually required to come up with a product or application. Combine that with the obvious need for the budget to burn on this research and (hopefully) development, and suddenly Science Fiction is just around the corner. We’ve even seen predictions where a price-tag was put (provisionally, of course) on an AI capable of replacing senior developers or even PhD level researchers.

The problem is that most people who read those predictions and claims, simply have no clue if any of it is actually achievable. What they do see is that many things have become possible that were definitely Science Fiction just a few years ago, and many companies with reputations for delivering on their promises are running around with the technology. This has happened before, but if we want to find something of a comparable scale, we’d have to go to the early “Internet Bubble” with the craze around Internet shops.

So let’s take a look at what is happening around AI, and specifically AI for software development. We’ll start with a look at what these products are trying to achieve and why this would be a game-changer. We’ll contrast that with what is actually possible at the moment, and I’ll admit even that is a moving target. Then we’ll take a short dive into how we got to where we are now, and what has changed in how we approach AI. But then we really need to talk about the technology behind the current AI engines, because it tells us what they can and can’t do. And that also tells us more about what we can expect from the future, and we’ll even touch on why Graphics cards have become so hideously expensive.

Ok, let’s start our tour of AI.

AI for Software Development or AI doing Software Development?

When the first plugins for IDEs appeared, they took the field by storm. Within a short time every major tool in the field had its own plugin. Sometimes backed by “the usual suspects” in Generative AI, but a few offering their own branded engines. That isn’t to say that deep down we wouldn’t find models from OpenAI, Anthropic, Alphabet, or Meta, but they’ll adapt or adjust it to fit their own lineup. Most AI coding tools are not trying to replace developers outright, even if some marketing slides will suggest otherwise. As I wrote earlier in my Blog, their biggest advantage is more subtle: reduce the repetitive work, boost productivity, and maybe even lower the barrier to entry for coding itself.

Autocomplete, refactor suggestions, test generation, and especially boilerplate scaffolding. These are things that soak up time and mental energy—and if AI can take care of those, developers are free to focus on the hard parts. That’s why this matters. If the tools work as promised, they’re not just assistants—they’re amplifiers. They don’t just save minutes; they could shift how teams plan, structure, and think about software development entirely.

Sure, experienced developers have also learned to be weary of the larger pieces proposed, as they’re also possible sources of rework. So, they’re great, if they work as advertised.

There’s no such thing as “AI”

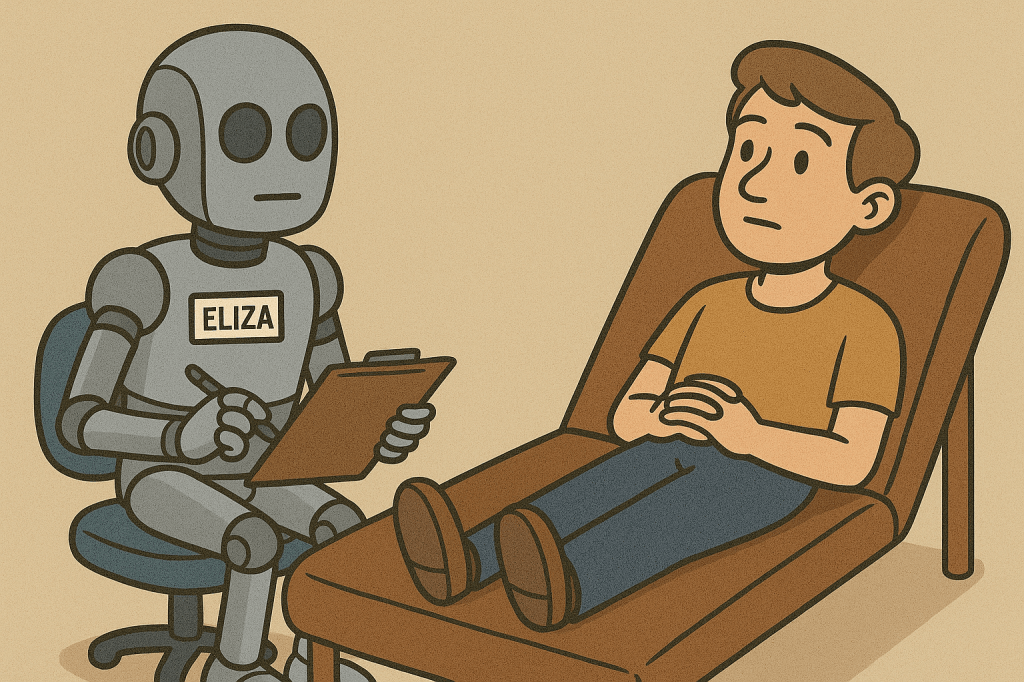

To start, let’s pull aside that moniker “Artificial Intelligence”, because it obstructs our view on a lot of very different tools and techniques. What we most often think about when we hear that term, is some kind of system that we can communicate with on the same level as we would with another human, without noticing that we’re not actually dealing with a human being. This is famously captured in the “Turing test” as formulated by Alan Turing. However, what has changed significantly over time is how we expect to achieve that level of “intelligence”. There was a likewise famous program called Eliza that attempted this by simply breaking the input from the human into words, matching those words with a fixed list, selecting the highest scoring match, and then responding by randomly choosing one of the associated responses. It used a small bit of knowledge of English grammar to be able to include parts of the input at an appropriate location in the response, but most users would quickly notice some repetition in the answers. It was amusing and could produce unexpectedly appropriate responses, but it was clearly not intelligent.

Expert Systems

The approach used by Eliza can be referred to as an “Expert System”. It has a collection of rules to choose from, finds the most appropriate one that is applicable to the input, and then applies it. There was actually a whole programming language designed around this concept, where a program would be written in the form of “if this holds, then that also holds” rules. The idea was that you can capture expert knowledge in such rules, present the system with some problem that you have, and let it try to infer which rules apply to see if it could draw any interesting conclusions. Because you would need to let it go through multiple iterations, each time extending the input with inferred additional conclusions, this approach required powerful systems for their work. They were applied to medical and legal knowledge bases to some success, but the obvious limitation is that it cannot find conclusions that it has not been fed.

Data Mining

If your knowledge is not in the form of such formalized rules, but instead a collection of values — either numbers or text — gathered over time, you can use various types of pattern recognition. Your input is not in the form of “if this than that” rules, but rather “this and that were observed at the same time.” Take information on banking customers, their accounts, and payments, supermarket inventory and sales, or all kinds of measurements on complex machinery. This lets you build huge collections of data that might provide useful insights. You could find that certain financial transactions are indicators of upcoming other ones, or help you detect indications of potential fraud. Or you could discover that diapers and beer often sell together at the end of the business day, indicating that, on the way home from work and asked to bring home some diapers, beer is a typical impulse buy. Or you could find which climate controls have a positive or negative effect on the quality of the product being assembled.

This approach is often referred to as “Data Mining”, as you’re digging through large collections of data to find valuable “gems”. Just like with Expert Systems it can bring valuable insights, but now we’re looking for things we didn’t know (or just had an indication of) were there. When we find something, we know what particular data items were involved, but we might not have any clue as to the why. Sometimes, as in the case of the sales of diapers and beer, we can reason backwards towards a likely cause, but the real cause may still be in data we’ve not captured.

Neural Networks

There are many more techniques that you can apply on your data to learn, and an important one we haven’t mentioned yet is the use of “neural networks”. With a neural network we don’t search for patterns in the data, but rather try to teach a particular pattern to our system. It uses a network of nodes that receive input and perform some processing on it to produce an output, and this can then be fed into another layer of the network. We then use a part of our data where we ourselves have provided the answer, “training” the network by telling it what we expect as output. Then we can feed the data without that answer a second time, to verify we get the expected response. Finally, we can either run further verifications with data not used during training, or just go for a real test.

This approach was applied with great success on problems such as image recognition, although there were some notable gotchas. For example, trying to recognize tanks in photos seemed to work fine, until it started to give false positives. This turned out to be caused by bad training data, as all photos with tanks also had clear skies, and the network had learned to trigger on the sky instead of that tank.

Neural networks have this reputation of being “just like a brain” in their structure and the way they function, but in practice they are mostly used as “simple” classifiers. They require careful preparation of the data to make it fit the network, and that tends to make the applications very specific to the problem they were developed for. The biggest “problem” however, if I may call it that, is that they cannot explain the reasoning behind their answers. They are an engineering implementation of a “hunch”.

Networks of networks

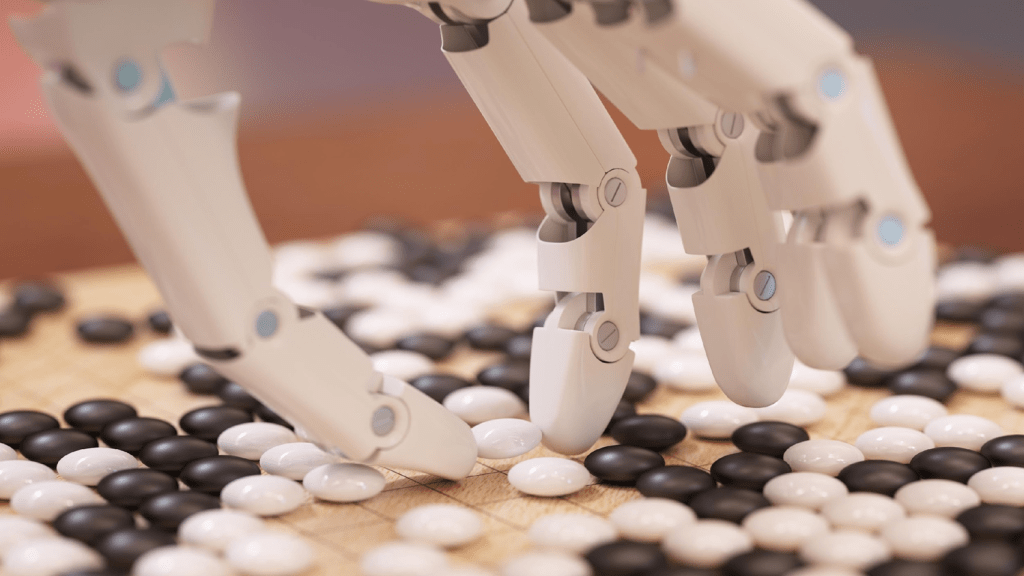

The game of Go has for years been the definitive problem for AI researchers, since it is a game of such complexity that a computer cannot reasonably be expected to iterate over all possible results, as IBM famously did for chess. Neural networks were attempted, but the large size of the problem usually meant that it was just one of the techniques used. Expert systems didn’t work either, as the ruleset was quite small, but the 19×19 board size again exploded the search volume. Researchers needed to to reduce the problem, so the inclusion of the Monte Carlo algorithm (disrespectfully referred to as “throwing the dice”) became a necessary addition, and the average amateur player could still win easily.

This all changed when DeepMind, by now a part of Google/Alphabet, decided to combine several neural networks on different aspects of the problem. Their approach brought them to fame when AlphaGo went on a winning streak that ended with it beating the reigning world champion. Professional players were amazed at what it did on the board, but perhaps also a bit gratified that the game analysis still required their expertise, because as a system based on neural networks, it could not provide answers on the “why that move”. Some moves were so blatantly bad that even DeepMind worried AlphaGo had started to hallucinate, only to realize later that for AlphaGo just a half-point difference was enough to win, so giving away large amounts of territory was perhaps unfortunate, but still not game-losing. And yes, AlphaGo already had this hallucination problem; we now know all chat-based AI systems are also prone to it.

Large Language Models or LLMs

So what if we made a huge neural network that, given some input, produces a single word. We build it so it selects that word based on the statistical likelihood that this word fits as the continuation of its input. We can then start with a sentence as initial input, generate the first word of a response, but then keep feeding the same input together with the generated output back into the network to generate the next word. If we first train the network on a huge collection of text, we get a system that will start producing text like its training data, but based on a start we provide. This is of course way oversimplified, but essentially the basis for what we now have under the moniker “Generative AI”. There’ll be alternatives that score pretty close to the selected answer, so a bit of randomization, Monte Carlo at play here as well, can help to ensure we are not too repetitive.

The next step is then to scale up in the volume of our training data, because we have a whole Internet chockfull of it, and we get to where we are now: systems that due to the humongous volume of data used for training, have a pretty large network capturing that knowledge, and are better if we can also scale up the amount of words fed into it on each iteration. The first is what causes the huge costs associated with training the model, the second is why a “local” model on PC, laptop, or phone, will not produce “as good” a result as one running on big cloud servers.

Is AI a Form of Graphics?

Now I haven’t really delved into the kind of processing that happens inside a neural network, but let’s simplify it by saying it’s mostly straight-on maths. By that I mean there is not a lot of data searches and complex logic going on, but rather (relatively) simple calculations on lots of data. A lot of that can happen in parallel, and it just so happens that matches well with the kind of processing power we use for displaying 3D graphics. Not so much that they wouldn’t benefit from a bit of specialized silicon, but you get the idea. A graphics card suddenly becomes an attractive bit of hardware to an AI developer. If you can do the training in such a way that you can simultaneously prepare the resulting network model to be optimized for such hardware, you understand why companies like NVIDIA, AMD, and Intel, suddenly start adding such support to their CPUs and GPUs. Also, since the companies buying that hardware in large quantities will be targeting servers and Cloud data centers, the small volume demanded by gamers suddenly becomes a nuisance, because their graphics cards are definitely not the same kinds of products.

What took the world by surprise is how well these LLMs can simulate a human conversation. From the dry perspective of a data scientist this is maybe just mildly surprising, because there is really a lot of training data available, but still, people were suddenly taking the field very seriously. The huge leap forward compared with the state of the art until that time, kind of suggested further leaps were just around the corner, especially since we could combine this new basic approach with all the other work done the past decades. Still, the amount of processing power to do this requires really deep pockets, so it’s not surprising there are only a few large players capable of building the core models. The rest picks up the “smaller” tasks of productizing or, such as with DeepSeek, piggybacks on this core group.

“They’re coming to take me away! Hihi… haha…”

Given that the Internet was built by computer nerds, it’s not surprising there is a lot of data in it concerning software development. Conferences, reference books, programming language standards, training, example code, and complete products with their source code. It’s all there, and it all gets sucked into the models. So rather than asking an AI to build an itinerary for your next holiday trip to Italy, you can ask it how to build a website on building itineraries, or ask it to explain this weird problem your code is having, and it will come up with surprisingly useful answers. Google was soon heard to claim 20 percent of their new code was written by AI, and developers started to worry about their jobs. At the same time, because the market for software development tooling is pretty lucrative, we started to see an explosion of AI coding assistants. And then something interesting happened.

In a review published in the yearly DORA report, developers were shown to be pretty positive about those new tools, and generally would hate to lose them. But they didn’t improve job satisfaction, and the code quality did not improve as dramatically as you’d expect. The writers of the report admitted they needed to look into these effects, but they suggested that the first might be from what replaced the time freed up by reduced work on coding, which might just be more meetings and non-coding work. But the second bit might play a role as well. Although the (bits of) code AI produced was saving time, it admittedly is a form of copy-paste reuse, and that has some well-documented weaknesses; Multiple copies of the same code potentially multiplies the amount of maintenance if that code needs fixes. Worse still, just as the Internet is full of useful bits of information, it also contains a lot of bad stuff.

A common effect is this:

Give me some code that does X

Here you are.

Thank you. But it looks like you made a mistake there

Ah, good catch. Thank you for pointing that out. Here is the corrected code.

Great, now add in Z

Here you are.

Ok, but we already had a solution for that. Please reuse that

...And so on.

In some cases you’re spending more time on formulating what you want than you’d have spent on writing it by hand, and that is not what we want to see. So instead of having the AI writing all our code, we use it for small bits that it can auto-suggest while we’re typing, while at the same time discussing the problem at hand and using it to provide ideas and suggestions. Another time-saver is what we call “Agentic AI”, where we can use natural language to describe tasks and actions, and let the AI actually do them.

“My AI doesn’t understand me”

However you apply Generative AI, at some moment you’ll run into this problem: “My AI doesn’t understand me.” You’ve spent a lot of time tweaking the prompt, providing more context, rewriting the question, but it simply refuses to do what you expect.

This is because, fundamentally, LLMs are not about understanding or applying knowledge. If you look at how these models deal with something as basic as “what is 1+1”, you’ll be horrified to learn it doesn’t do maths at all, and some of the intermediate results in its network make absolutely no sense whatsoever. Similarly, when applying AI to software development, it doesn’t build a mental model of the requirements and translates that into a framework for an implementation. The AI just slogs through repetitive generations of words and symbols that happen to result in a piece of working code, if the statistics work out. When they go wrong, the AI hallucinates, and all bets are off.

But for the most part, this is fine. Specialized models may be “decorated” with additional checkers and context retrievers. That helps. And, most of the time, it will do what is expected of it. But the funny thing is, when we add “rules files” stipulating common requirements to our interactions with the AI, we’re not actually adding logic to verify if the results are acceptable, nor do we extend the generation process with additional knowledge. In a sense, we’re adjusting the weights on alternative continuations, making some replies more likely than others. Depending on the training data that went into the model, some phrasings will turn out to help better than others. Logical consistency in those rules may help you to get better results, but don’t expect the model to apply logic or check consistency itself. It only knows what usually follows on its input.

So is AI worth its money?

This is the “million dollar question” about AI, and in my opinion the bit that nobody wants to talk about. Ask a developer who develops “at home”, and they will tell you they use it all the time. Free ChatGPT accounts or plugins in their IDEs, maybe even locally running small (and free) models on their graphics cards, there’s a lot that can be used. You could even argue that paying a small amount for a commercial product is worthwhile, if only for the additional experience it gains you that might help with paid work. But at most this pays for running those models, not the initial training. And the “is it worth it” question has two sides; the first is for investors and the “AI companies”, the second is for the customers, either IT managers or their developers.

The first group is in here for the long run. They know they need to sink in gobs of capital to get a good return, even giving away simplified versions of their services to build critical mass.For a company like Microsoft, the Return On Investment comes with increased sales and support on their applications and cloud services. Some companies even freely distribute full versions of their models, because the required specialized hardware and support won’t necessarily cause a cut into their target market. They need the reputation, the publicity, and market penetration. They can even afford to over-promise, as long as it’s clearly discussing the future, because it hooks potential future customers.

On the customer side, especially for developers, we already know the answer; as long as it’s affordable they’re hooked. They’ll quickly learn where it helps and where it’s just rubbish, and even if the free thing is just part of the solution, on the Internet almost any itch eventually gets scratched. For the IT manager the situation is less clear; If the goal is to solve a KPI called developer productivity, the commercial offerings may turn out to provide a real challenge for the ROI. Don’t forget, the runtime costs of AI are pretty substantial in themselves, so an “Enterprise” license for an AI coding solution may be a bit big to swallow. But refuse to pay up and you’ll find your developers use unlicensed or unapproved solutions in the shadows instead, and that is not an ideal situation either. Block it totally and you might find your talent looking for alternatives, and that is an even bigger problem, because that AI won’t fully replace your IT staff, and citizen developers, as non-IT staff is sometimes referred to, might fail to catch the mistakes.

So is AI worth it? That ultimately depends on who’s asking, and what problem they’re trying to solve. So instead, let’s ask ourselves “what does AI mean to me?” It’s not Artificial Intelligence, but, just like the Internet, it’s a force multiplier. Use it well and it can do wonders, but be wary and always keep your feet firmly on the ground.